ING in The Economist and Fortune

In recent articles in The Economist “Slim, trim and solvent, ING is looking to regain disruptive mojo” and Fortune “ING Group: The slimmer, stronger giant” CEO Ralph Hamers talks about ING’s new strategy; “We were the disruptive challengers”.

The articles describe how ING emerged from the financial crisis. Economist; “ING is now a bank with almost €800 billion in assets, primarily in the traditional business of raising deposits and granting loans.

The retail bank, centred on Europe, accounts for around two-thirds of its income and the global commercial bank for the rest. ING operates as a branch-based universal bank in its core Benelux market and in Poland, Romania, Turkey and bits of Asia. It’s still owns a big online banking operation in Australia and much of Europe, called ING Direct.”

In Fortune CEO Ralph Hamers explains mobile banking is not at straight forward as you might think “It’s a completely different experience, with different expectations. It sounds very simple to offer easy banking, but there’s a lot to it.”

Read The Economist article below and read here the Fortune interview.

Up and at ‘em

Slim, trim and solvent, ING is looking to regain its disruptive mojo

Oct 4th 2014 | AMSTERDAM |

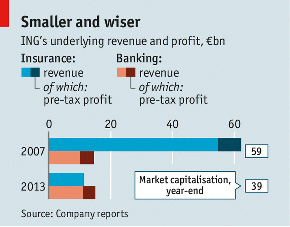

The Economist graphic - smaller and wiser: ING's underlying

revenue and profit

LESS than a decade ago ING Group, with its orange lion logo, was the epitome of finance rampant. Its banking, insurance and asset-management activities sprawled across the globe. Today, as it emerges early from a state bail-out precipitated by its large portfolio of American mortgages, it is again an example—this time of the sort of institution that new, more demanding prudential rules encourage.

ING is now almost entirely a bank, more focused than before on Europe, with total income in 2013 around a third of that in 2007. While rivals such as Commerzbank or Royal Bank of Scotland still struggle to adapt to the new regulatory strictures, ING is ready to roll.

It has meant wrenching change. ING promptly repaid €5 billion ($6.3 billion at the time) of the €10 billion the state injected into it in 2008, raising €7.5 billion to do so. Further repayments followed, along with hefty interest and fees. A final €683m in principal is likely to be repaid ahead of schedule this year, assuming the European Central Bank’s impending review of big banks’ books goes well. The state will have earned a tidy €3.5 billion on its loans, plus €1.4 billion on the €24 billion in American mortgages it took off ING’s hands.

Still harder were the requirements of the European Commission, which told ING to hive off insurance and shrink. It sold off not only insurance operations from Argentina to South Korea but also direct banking in America, Canada and Britain, private banking, asset management, custody services and more—conducting more than 50 transactions in five years, says Patrick Flynn, its chief financial officer.

It still owns 32% of its American insurance arm (floated in 2013 as Voya) and 68% of the European-cum-Japanese version (floated in 2014 as NN Group), but will sell down the latter from January. Including the market value of the insurance stakes it still holds, ING realised some €40 billion.

The money was used to boost the regulators’ favourite sort of loss-absorbing capital to 10.5% of the bank’s assets, plug an €8 billion hole in the holding company balance-sheet due to losses on its stakes in its subsidiaries, strengthen the capital position of the insurers and of course repay the state.

Today ING reckons it has around €5.5 billion in excess capital. It plans to resume dividend payments by mid-2015. The bank is more efficient than it was: its cost/income ratio in 2013 was 35% lower than in 2008. It is also safer: though non-performing loans rose slightly in the first half of 2014, risk costs overall are declining.

What next? ING is now a bank with almost €800 billion in assets, primarily in the traditional business of raising deposits and granting loans. The retail bank, centred on Europe, accounts for around two-thirds of its income and the global commercial bank for the rest. ING operates as a branch-based universal bank in its core Benelux market and in Poland, Romania, Turkey and bits of Asia. Its still owns a big online banking operation in Australia and much of Europe, called ING Direct.

Ralph Hamers, the ING lifer who became its chief executive last year, is betting on technology to expand existing businesses rather than acquiring new ones. ING Direct was ahead in its day, hoovering up deposits in new markets under the noses of stodgy rivals. “We were the disruptive challengers,” Mr Hamers says.

Using those deposits is getting trickier, however. Though ING’s loans are almost fully funded by deposits overall, that is not the case in each market, points out Koos Timmermans, vice-chairman of the management board. In Germany, where ING is the third-biggest private bank by customers, ING had €107 billion in deposits at the end of 2013 but only €71 billion in loans.

The reverse was true in ING’s home market, where there is a perennial funding gap because the Dutch save more than most through pension plans and have been encouraged by tax breaks to take out mortgages. Since the crisis many national supervisors have made it hard to move retail savings across borders to fund lending elsewhere. This traps pools of liquidity, forcing banks to borrow on wholesale markets despite having money to spare.

After the ECB takes over supervision of Europe’s biggest banks in November such barriers may fall. But ING is leaving nothing to chance. Its focus is on increasing loans in markets where savings are plentiful, especially to consumers and smaller firms. The approach is bearing fruit in Germany and in its infancy in Spain. ING no longer has the element of surprise; most banks are investing billions in technology. But having restructured in record time, it may be quicker off the blocks.